‘Starting in the middle’ is an idea that comes from post-qualitative research. Post-qualitative research has a sort of cult-following, there are people that get it and people who get really worried, call your folks and won’t rest until you start being a normal scientist again. Anyway. Here, at the official start of the project I am supposed to say something about methodology. I’ll try to do that now without going too far down the rabbit hole. Post-qualitative research is characterised by irony and postmodern concerns. For example, when an observer realises she is unavoidably part of what she observes, it becomes illogical to speak about the object of study without including the speaker herself. This self-consciousness unravels the objectivity of the work, particularly in dynamic, messy contexts like communities and landscapes. What works for a Petri dish doesn’t work for a community lead research project.

The post-qualitative researcher is not against data or the scientific method, but aware of the limitations of modern scientific methods in some fields of study. This research is about using willow to afford protection to small tree plantations. One of the research questions is this: will a roe deer bother to break through a willow fedge or not? A modern, traditional scientist might think that given enough controlled conditions a roe deer, a willow fence and a tree plantation could be experimented with. But we’re not interested in whether the roe deer breaks through a willow fence in controlled conditions, or even “in nature”, we are interested in the feral, messy zones where semi-wild roe deer live in the Scottish lowlands. We have an experiment but our results won’t be fully objective - we won’t have graphs or equations that we can say are reliable. We aim to convince you simply that we were here and we know what happened.

Post-qualitative research papers often think aloud about methods - of their deliberate lack of them. This “no-method” method can feel like a ritual, as if crafting a worthy word-spell might summon authority. Anyway, I’m not going to spend a long time on it, except to say - here is a narrative to go along with the photographs and the other evidence - I hope you enjoy it - and it is what it is.

We are starting in the middle with many things already in progress: 4 years of willow fedge growth and 7 years of nature restoration attempts. It’s hard to separate myself from the places I’m trying to study. I no longer have a methodology that exerts itself from outside the project at all. Instead, ideas, actions, people and places connect like a rhizome of roots. I can only work from the inside constantly throwing out connections to try to get a wider perspective.

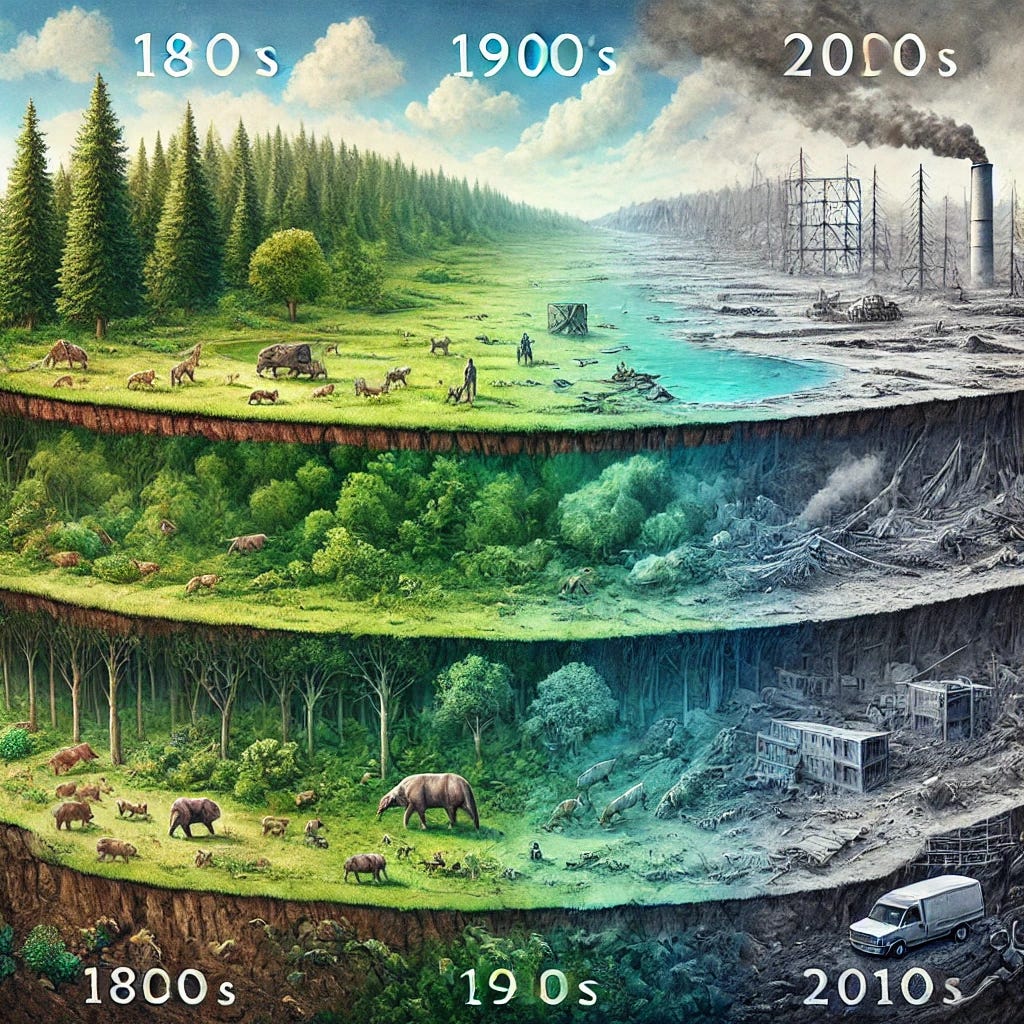

Don’t worry, it’s just stories and results from here on in. Maybe you’ve missed the start but we are both here now. Just as our research begins in the middle, so also do the stories of the landscapes. These ‘middles’ - or baselines - offer a way to measure change. An ecological baseline helps us track the health of a place over time. But where should we set that baseline? This question also brings us to the concept of shifting baselines and the trouble they hide.

From my first baseline to the new science of rewilding.

I first learned about making baselines when I trained to be a cartographer. A baseline is the most accurate measurement you can make on a map because all the other measurements depend on, or are statistically adjusted to, that baseline measurement. Across the world, the Ordnance Survey set theodolites on triangulation pillars, measuring baselines from mountain-top to mountain-top. These lines formed the foundation of accurate maps. The days when cartographers got paid to climb mountains and draw triangles were the good old days. At one time, I wanted to be one of the last real cartographers: climbing hills, writing in rain-soaked logbooks and trying not to drop the equipment… Now we have Google maps and I have a different kind of baseline to think about, but think what it would mean for maps if the baselines could move. The idea of the shifting baselines effect describes a fault in our humanity, and to correct that error is to draw a map beyond the human and to embrace rewilding as a new science.

Before exploring the shifting baselines effect, it’s important to define what ecological baselines represent. Ecological baselines are a measurement of biodiversity, natural habitats and animal populations. If we want to say that nature is changing at all, we need to measure that change from some point in time and from some place. Talk about baselines elicits some idea of when things were normal or natural.

The first ever point in time is, of course, 15 billion years ago when there was a sort of pregnant silence. Then, the Big Bang unrolled reality as we know it. If we consider the baseline of existence itself, the birth of the cosmos, then the biodiversity of today is extraordinary - a triumph of life against the odds. But using such an expansive point of view minimises the urgency of our times. The Big Bang is an absurd place to start, but it highlights how the choice of a baseline shapes the ecological stories we tell.

If we set our ecological baseline to the mid-20th century, within our collective human memory, we see a different picture. Bird populations overall in the UK have declined by 50% since 1970, there is a lot less of every wild thing. It’s not nice to think about, so we try not to think about it most of the time. My father, Eldon carried memories of a rural Bermuda bursting with life - a place I can barely imagine now. With his passing, those recollections have faded away, leaving younger generations with a shrunken sense of what ‘abundance’ really means.

So the shifting baselines effect describes how each generation percieves the environment they grew up in as ‘normal’ and forgetting - or never knowing - the richness of what came before. Over time, this erodes our collective awareness of ecological loss. This is nothing new. In Australia, the first human inhabitants wiped out 90% of the megafauna, but they likely didn’t notice - they took over 1000 years to do it. Even now, people say that they haven’t actually noticed nature decline in their lifetime, in fact, yesterday they saw a deer on the road, how about that? This sort of blindness is a fact of human existence and is what’s wrong with being people-centred. When we place humanity at the centre of all things, we limit our ability to measure - or even care about - what lies beyond the human horizon: the environment, biodiversity collapse and the climate crisis. The shifting baselines effect reminds us of this limitation, showing how each generation unconsciously adjusts its expectations to fit a degraded world.

At this point, I could tell you about something that upsets me: I’ve watched a part of the ocean die. It’s heart-breaking to actually see an ecosystem collapse. I’m sure many people like me have the same lived experience of not being protected by the shifting baselines effect, of seeing an ecological collapse in one’s own lifetime. Each year I went back to the same places and swam. There the rainbow of coral and fish and other wildlife I remembered was degrading in an odd progression of ways, replaced by emptier and emptier water. And yet, even now, people still snorkel there. I see them watching a shoal of grey sardines in cloudy water. I hear them marvelling at the wonders of nature and how they saw one sea turtle. Children accept the world as it is so I bite my lip. I’m over 50, the world is not what it was, it is no longer acceptable as it is. In the shipwreck of my old skull, I am haunted by rainbow-coloured ghosts - reminders of a world that has faded and a baseline I can no longer swim in. These fading rainbow fish can’t swim against time. I want them to come back, but that’s impossible. The ghosts of the fish stare at me reproachfully from behind bleached coral brains. I remember, I ate some of them and now I see things from their point of view.

The shifting baselines effect reminds us of the losses we’ve grown accustomed to, but where should we set our baselines to imagine restoration? This is where the science of rewilding offers a new perspective. Let’s say my baseline started in 1980, when I was seven and swimming in Bermuda. I say I’ve seen a part of the ocean die over the last 40 years. If I could see that part of the ocean in 1880 or 1780, I think I would be even more upset. There would be more rainbow ghost fish the further back I went. Only when we get back to a point when there was a minimal human impact will the ghost fish stop gathering around me.

A point in time in the past when there was little or no human impact on the ecosystem is where rewilders set their baselines. At the end of the last ice age, around 10,000 years ago, Europe’s landscapes were home to megafauna like woolly mammoths and woolly rhinos, thriving in ecosystems as wild and as untamed as today’s African savannas. This pre-human baseline offers a starting point for addressing post-human challenges like climate change and ecological collapse.

Rewilding challenges us to think beyond our own lifetimes, to imagine a world where ecosystems flourish once more. It offers a baseline not only for restoration but for reconnection—with nature, with time, and with the ghosts of what we have lost. The rainbow fish may never return, but in rewilding, there’s a chance to create something new: a place where nature can make some gains.

The new science of rewilding has shifted our understanding of what nature would be like if we had never existed. Of course, we plan to exist with nature but for the sake of the relationship it matters what nature’s baseline is. Rewilding scientists tend to think about what things looked like after the last ice age 10,000 years ago. Those who love trees are tempted to think that world looked like a closed canopied forest. The blockbuster movie, Avatar (2009), imagined a max-ed out jungle world and invited us to do the same. The film’s vision resonates - but it’s misleading.

Re-imagining our ecological baseline.

In reality, the post-glacial UK was a mosaic of habitats shaped by the interplay of megafauna, predators and vegetation. There were megafauna that dismantled and consumed trees. Enormous deer, auroches (huge cows) and bison created grasslands. Trees survived not only because of their adaptations but also because predators - wolves, cave bears and sabre-toothed cats - created a landscape of fear, keeping herbivores in check and allowing forests to coexist with open grasslands.

In our baseline world, the carnivores are very picky and most carnivores are themselves someone’s prey. Most carnivores aren’t interested in what they could catch, they are noble, niche predators interested in a particular prey species. In this way, incredible population densities exist at this time, and rather than being a riotous assembly most animals basically ignore each other, concentrating only upon their most important concerns. Let’s try to imagine how that looked.

It’s dawn in the grassland, a mouse finds a seed to eat and stops out in the open, it’s a slight error on her part. A kestrel hovers overhead, it senses the mouse and adjusts its position for a better look. But it catches the silhouette of a sparrow-hawk on the edge of its vision. The sparrowhawk’s approach is interrupted by a goshawk, which swoops suddenly. Goshawks hunt sparrow-hawks — but today this one is diving for cover. A golden eagle passes high above. Golden eagles will go for a goshawk but for now, no one is getting a meal - except the mouse.

The mouse lives in a landscape of fear. He is in fear of the kestrel, a small raptor - who fears specialist hunters of small raptors - sparrowhawks - who fears hunters of specialist hunters of small raptors - goshawks - who, in turn, have good reason to fear golden eagles. Such food webs allow populations to be high and to balance. Animals are everywhere and kills are effectively restrained. Only the young, the old, the sick and the careless are in danger. The hard rules of the Holocene apply to everyone. It is cruelty, but these inhumane rules afford many lives, and many kinds of lives, to be lived.

The soil too is clearly alive. Its top layer soft and crumbly, teeming with insects and worms. There are minibeasts that draw down the dung, and the carcasses, of megafauna. Each movement enriches the ground, creating a fertile foundation for grasses and trees. Below, the fungal network links plant roots, forming a silent, subterranean web that sustains the life above. This cycle of decay and renewal anchors the mosaic of habitats, a testament to the interconnectedness of the post-glacial world. But even in this baseline paradise, life happens on a very thin layer of vibrant topsoil which lies on top of completely dead rock.

Muiredge Park, 2024.

Muiredge Park isn’t the Holocene soil of 10,000 years BC. Muiredge Park 2024 is a middle and it is a place of the Anthropocene. Humanity is the dominant force shaping the planet, and a stable Holocene climate has given way to climate chaos. The contrast between the post-glacial Holocene baseline and our corner of an unstable Anthropocene ‘middle’ is stark. At a glance, Muiredge Park is grassland but it’s nothing like the grasslands of our baseline - it’s empty land, haunted by ghosts of species passed - but maybe, human hands can plant a better future.

Unlike the ocean, which we understand as constantly moving, we often think of land and soil as static and unchanging. But that is yet another case of the shifting baselines effect: Muiredge Park has been reshaped by human hands over hundreds of years, a timeline beyond the human hippocampus. Its strata bear unmistakable Anthropocene finger prints: rock and broken clay from mines below, bricks and broken tiles, and more recently, plastic bottles and vapes. Beneath the grass, the layers are already churned over and mixed and even the ghosts are buried in human debris. When we look at our post-glacial baseline world and then consider restoring nature in a small park in a Scottish town, it seems impossible. A full nature restoration at Muiredge Park is, of course, beyond us. Still, rewilding dreams big and acts local. By restoring nature where it can be restored, we participate in a larger story of renewal across the world — a story that I hope is as dynamic and complex as the ecosystems we hope to revive.

Understanding these shifts in baselines sharpens our perspective on the challenges of restoration. In the Anthropocene, Muiredge Park has been shaped by centuries of human violence. I want to describe how far Muiredge Park has sunk from that Holocene baseline ecosystem - its wooly mammoths and spectacular food webs. I’ll attempt to describe it, starting underground.

Nobody knows but I suspect that thirty meters below Muiredge Park lies salt water, in inky blackness, rising and falling with the tide. I once found a place where you could drop a stone and hear the splash 30m below—until the National Coal Board came to seal it. There’s a story about how the local school’s concrete foundations kept disappearing into the ground as they were building it. Apparently the liquid concrete made its way to Rosyth and that’s why the school got built next to the main road. Whether that’s fact or legend, it illustrates the instability now below us.

The surface layers tell their own story. By 1945, the Holocene topsoil had long been buried. Aerial photographs from the time show a tree plantation and a miner’s rest home, planted to cover centuries of mining debris. That tree plantation was an earlier effort to reclaim this land from polluted death, nature restoration isn’t a new idea. By 1952, the plantation was replaced by housing, a school, new landscaping and a smell of unknown origin called the “Methil Ming”. Now, the grass is a monoculture of weeds, choking out competitors except for daisies, cuckoo flowers, and dock. If you dig, you’ll find junk, rubble and clay. The grass will one day create an healthy topsoil, but that process will take thousands of years.

From the sky, microplastics rain down as ghosts of airborne microbes passed, tainting the warming air. The Holocene was marked by a stable climate; now the Anthropocene brings turbulence. The sky is still blue, but it bears little resemblance to the sky of the baseline world. From ground to soil to sky, Muiredge Park is far removed from our post-glacial baseline.

And biodiversity? I almost haven’t the heart to begin. The abundance of that baseline world has collapsed, leaving this grassland as a shadow of what once was. Deep underground the ghosts of woolly mammoths, aurochs and bison roam on that magical thin layer of soil now turning to stone.

All the same, I shouldn’t romanticise that post-glacial landscape without tempering it with relief. I’d have been doomed — a slow, easy target for wolves, cave bears, or saber-toothed cats. In that landscape of fear, survival depended on youth, strength, and speed. While rewilding is inspirational, I don’t want to see bears the size of horses eating our youngest, our oldest and our unluckiest citizens.

Rewilding doesn’t demand a full return to that baseline world, and nobody is happier than me to tell you this. Last night I woke up from a dream where a dire wolf the size of a pony crunched up my skull like it was a dog biscuit. That’s not rewilding. That’s a nightmare. But rewilding is about releasing the imagination, encouraging biodiversity where we can and creating new layers of resilience in our Anthropocene landscapes. In Muiredge Park, we are going to explore a few possibilities for nature restoration that don’t involve living with dangerous carnivores.

CONCLUSION

The shifting baselines effect reminds us of what we’ve lost—and what we risk forgetting. It’s a sobering lens through which to view our world, but it doesn’t have to be paralysing. If we listen closely, the land itself offers clues about how to begin again.

In a small corner of the Anthropocene, Muiredge Park bears the scars of centuries of human activity. Its history is layered in coal, clay, and rubble, with soil that feels as distant from the Holocene as the ghosts of the woolly mammoths it once sustained. Yet we choose to believe that some nature restoration is possible.

The next post, is the story of experimentation, failure, and the development of the Willow Worlds idea — a story of a land in a recovery position and humans who try to speed up the process, bringing it back to health. From Bat’s Wood to the Willow Worlds, I’ll describe the journey as best as I can.

POSTSCRIPT.

On learning to live with the local wildlife. An informal reaction to some territorial leg-raising which has again been sprayed onto our shed.

“STAZ - your artwork is improving, but I still have to paint over it.”